Table of Contents

Beginning, Course, and Termination of Popliteal Artery

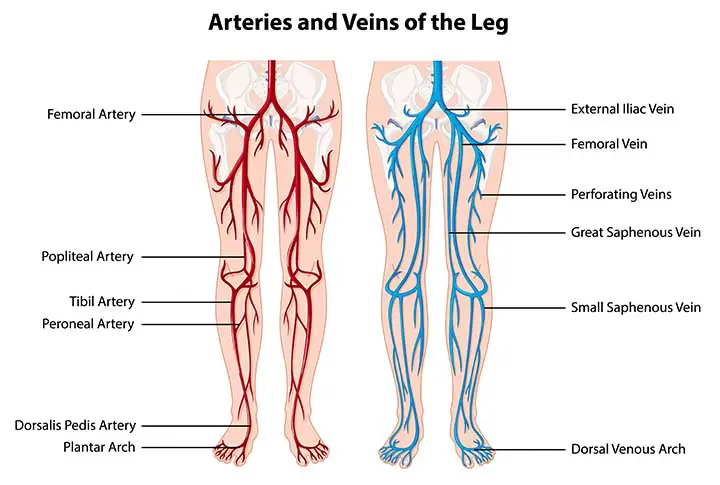

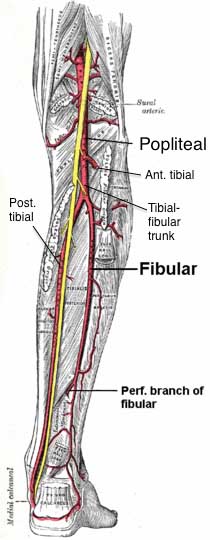

The popliteal artery is a continuation of the femoral artery. It starts at the gap in the adductor magnus or hiatus magnus, i.e. at the junction of the middle and lower thirds of the thigh.

It runs downward and slightly laterally until it reaches the popliteus’s lower boundary.

It divides into the anterior and posterior tibial arteries at the lower boundary of the popliteus.

Read Popliteal Vein

Surface Marking

The Popliteal Artery is marked by connecting the following points.

- First point: 2.5 cm medial to the midline on the back of the limb, at the junction of the middle and lower thirds of the thigh.

- The second point is on the back of the knee’s midline.

- Third point: At the stage of the tibial tuberosity, on the midline of the back of the neck.

Read Popliteal Fossa

Relations

The popliteal artery is the deepest structure in the popliteal fossa. It has the following relations.

Anterior or deep to the artery, from above downwards,

there are:

- The popliteal surface of the femur.

- The back of the knee joint.

- The fascia covering the popliteus muscle.

Posterior or superficially: To the tibial nerve.

Laterally: Biceps femoris and the lateral condyle of the femur in the upper part, plantaris, and the lateral head of the gastrocnemius in the lower part.

Medially: In the upper section, semimembranosus and the medial condyle of the femur. In the lower portion, the artery is linked to the tibial nerve, the popliteal vein, and the medial head of the gastrocnemius.

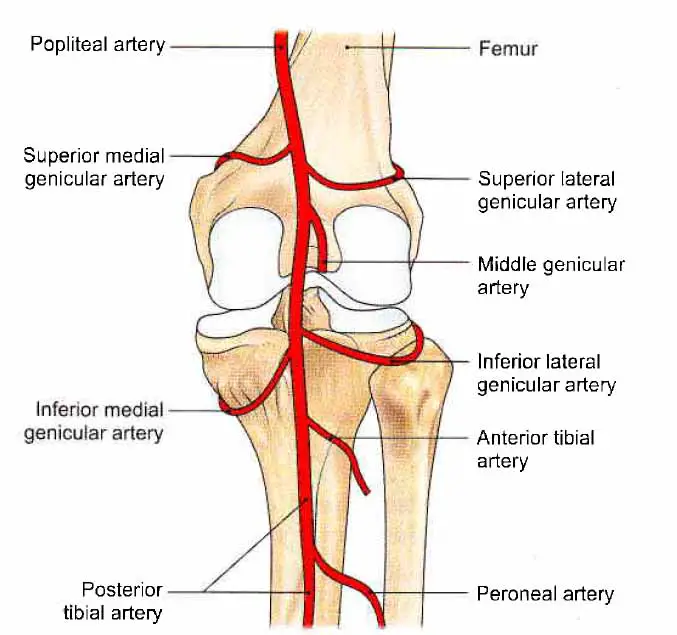

Branches of Popliteal Artery

Branching Several big muscular branches develop. Upper (two or three) muscular branches supply the adductor magnus and hamstrings before anastomosing with the fourth perforating artery. The gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantaris are supplied by the lower muscular or sural branches.

Cutaneous branches originate either directly or indirectly from the popliteal artery’s muscular branches. The small saphenous vein is normally accompanied by one cutaneous branch.

There are five genicular branches:

- Superior lateral genicular artery

- Superior medial genicular artery

- Middle genicular artery

- Inferior lateral genicular artery

- Inferior medial genicular artery

The cruciate ligaments and the synovial membrane of the knee joint are supplied by the middle genicular artery, which pierces the oblique popliteal ligament of the knee.

The medial and lateral superior genicular arteries wind along the respective sides of the femur, just above the corresponding condyle, and travel deep to the hamstrings.

The medial and lateral inferior genicular arteries wind through the corresponding tibial condyles before passing deep through the knee’s collateral ligaments. Both of these arteries reach the front of the knee and help to shape the anastomoses that surround it.

The sural arteries are large vessels that emerge on either side of the popliteal artery and supply blood to the gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantaris muscles.

The popliteal artery divides into the anterior and posterior tibial arteries as it reaches the inferior boundary of the popliteus muscle.

Read Peroneal Nerve

Surface Marking of Tibial Arteries

Anterior Tibial Artery

It is marked by connecting the two points mentioned below.

- First point: 2.5 cm below the medial side of the fibula’s head.

- The second point is located halfway between the two malleoli. The artery runs downward and slightly to the medial side.

Posterior Tibial Artery

It is marked by connecting the two points mentioned below.

- The first point, locate the tibial tuberosity in the midline of the back of the leg.

- The second point is located halfway between the medial malleolus and the tendocalcaneus.

Read The Tibial Nerve

Clinical Anatomy

- The popliteal artery is used to measure blood pressure in the lower limb. The popliteal pressure is lower than the brachial pressure in aortic coarctation.

- Constant pulsations of the popliteal artery against the unyielding adductor magnus tendon can cause changes in the vessel wall, leading to artery narrowing and occlusion. Sudden occlusion of the artery may cause gangrene up to the knee, but collateral circulation through the profunda femoris artery normally prevents this.

- A fibrous band located just above the femoral condyles secures the popliteal artery to the capsule of the knee joint. This may be a cause of constant traction or stretching on the artery, resulting in primary thrombosis of the artery in young people.

- When the popliteal artery is compromised by atherosclerosis, the lower part of the artery is normally patent, allowing grafts to be attempted.

- The popliteal artery is more susceptible to aneurysms than many other body arteries.

- Popliteal artery hemorrhage: While dislocation of the knee is rare, it may occur as a result of extreme, high-energy trauma or a powerful force applied to the joint. Because of its proximity to the joint, the popliteal artery is at risk of being affected after knee dislocation. When the knee dislocates, the popliteal artery is stretched, causing it to contuse, tear, burst, or split fully. This can then cause damage to the popliteal vein as well as the calf muscles. Without treatment, this can result in limb loss.

- Popliteal artery entrapment syndrome: The popliteal artery connects the two heads of the gastrocnemius muscle in the lower leg. Any changes here can cause intermittent claudication (pain caused by inadequate blood supply) during muscle contraction. This causes repeated damage to the popliteal artery, which can lead to arterial thrombosis and thromboembolism or the development of aneurysms.

The popliteal artery entrapment syndrome is graded based on the origin of the compression of the popliteal artery. Types 1 and 4 are caused by anomalies in the popliteal artery’s direction, while types 2 and 3 are caused by an irregular insertion of the gastrocnemius muscle’s medial head. Form 5 is entrapment of both the popliteal artery and vein, while type 6 is compression of the popliteal artery during leg movements but without any anatomic abnormalities.

The popliteal artery is surgically released by myotomy (muscle removal) of either the medial or lateral head of the gastrocnemius.

Common Clinical Questions

How is blood pressure in the lower limb taken?

Ans: The blood pressure in the lower limb is measured by auscultating the deep popliteal artery. The patient must be in the prone position. The wider cuff is fastened across the calf. Pressure is gradually applied and released. On the popliteal artery, auscultatory sounds are heard.

What could be the cause of low BP?

Ans: The cause may be “coarctation of the aorta,” which is a narrowing of the aorta that reduces blood flow to the lower limbs, resulting in a drop in blood pressure. The coarctation must be surgically treated.

Popliteal Artery Diseases

Atherosclerosis

The most common cause of popliteal artery occlusion or stenosis is atherosclerosis, which is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Atherosclerosis pathogenesis is well understood. The endothelial injury starts a chain reaction that results in the overproduction of cellular mediators, which leads to the formation of fibrotic plaque. This plaque can calcify, crack, ulcerate, and hemorrhage, eventually limiting blood flow or causing vessel thrombosis. Smoking, diabetes, advancing age, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, male gender, and a family history of the disease are all risk factors for atherosclerosis.

Depending on the severity of the disease, patients can present with a variety of symptoms. Intermittent claudication is a typical symptom of a single-level disease. The multilevel disease can be characterized by more serious ischemic symptoms such as rest pain and tissue loss. At or below levels of major illness, the patient may have a reduced or absent pulse on physical examination. Where there is severe stenosis, bruits may be auscultated.

Color duplex ultrasonography (US) and an ABI with segmental lower-extremity arterial pressure readings or pulse volume recordings are examples of noninvasive arterial studies. These studies are inexpensive and can aid in the localization and seriousness of the lower-extremity arterial disease. MR angiography may provide noninvasive, arteriographic disease localization, but at a higher cost. The diagnostic precision of gadolinium-enhanced three-dimensional time-of-flight MR angiography is comparable to that of normal contrast material–enhanced angiography. High-quality imaging necessitates a certain degree of experience and is ideally accomplished by the use of stepping or sequential imaging with multiple injections. Variable runoff times and picture loss at the trifurcation due to venous filling are still issues. Where endovascular or surgical intervention is needed, conventional angiography is typically performed.

Angiography will reveal atherosclerosis as irregularities in the vessel lumen, such as stenosis or occlusion. When atherosclerosis is the cause of popliteal artery stenosis or occlusion, similar vessel irregularity is observed in the peripheral runoff. With popliteal artery occlusion or severe stenosis, collateral arteries will reestablish distal runoff over time. Sural or genicular branches of the deep femoral artery are commonly used to provide collateral vessels for the more distal popliteal or trifurcation vessels.

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA), thrombolytic injection, and, less often, stent placement are typical interventions for lower-extremity atherosclerotic disease. Pentecost et al created a classification scheme for popliteal and superficial femoral artery disease in collaboration with an American Heart Association task force to help determine if PTA or surgery should be used.

Thrombolytic therapy can be used to treat acute and subacute popliteal artery occlusions caused by underlying stenosis. Thrombolytic therapy is most effective when started within two weeks of thrombosis. The catheter with multiple side holes is placed across the occluded segment to begin therapy. A lytic agent must be continuously infused for 8–36 hours, with occasional follow-up angiography. Stenoses are often discovered and handled with PTA.

Primary stent placement in the popliteal and superficial femoral arteries is not recommended due to low long-term patency rates. In cases of failed PTA, stent placement in the popliteal artery should be preserved. Because of the popliteal artery’s superficial position and worries about extrinsic compression, self-expanding stents should be used. Surgical treatments usually include bypass grafting and, less often, endarterectomy and patch angioplasty. A vein graft outperforms a synthetic graft when the popliteal artery is bypassed below the knee joint.

Popliteal Artery Aneurism

Aneurysms may be classified as either true or false. True aneurysms develop when all layers of the arterial wall dilate unusually. False aneurysms (pseudoaneurysms) are caused by an arterial wall defect caused by trauma or (mycotic) infection. Trauma can be caused by iatrogenic injury as a result of surgery or intervention.

If the diameter of the popliteal artery reaches 0.7 cm, it is called aneurysmal. Aneurysms are rarely associated with connective tissue disorders like Marfan syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and much less often with pregnancy. Almost all genuine aneurysms are asymptomatic. Historically, the nonspecific type of aneurysmal disease that affects the abdominal aorta as well as the iliac, femoral, and popliteal arteries was referred to as “atherosclerotic.” Risk factors for the atherosclerotic disorder are also linked to nonspecific aneurysms. However, atherosclerotic disorder and these risk factors only provide a partial picture of the cause of these aneurysms, which tend to be multifactorial.

The most common form of peripheral arterial aneurysm is a true aneurysm of the popliteal artery. Popliteal artery aneurysms (PAAs) are less frequent than abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs), but recent researchers have confirmed a rise in the incidence of PAAs, which may be attributable to increased access to imaging modalities such as the US. As a result, studies differ on the ratio of PAAs to AAAs, which varies from 1:8 to 1:23. PAAs are linked to aneurysms in other parts of the body. An AAA is found in 30–50% of patients with a PAA. PAAs, on the other hand, were found in just around 10%–14% of AAA patients. In 50–70% of cases, PAAs are bilateral. These relationships have significant ramifications. It is important to look for AAAs and a contralateral PAA in patients with a PAA. PAAs are most common in the sixth and seventh decades of life and have a heavy male predilection, with a male: female ratio varying from 10:1 to 30:1.

Because of the possibility of limb-threatening thrombotic complications, it is essential to treat PAAs. At the time of diagnosis, approximately 45 percent of patients with PAAs are asymptomatic. Lower-extremity ischemia manifests as claudication, rest pain, or extreme ischemia associated with thrombosis or embolization in symptomatic patients. In general, the US is the most widely used and effective imaging modality for diagnosing PAAs. The US will assist in determining the presence and patency of an aneurysm, as well as whether the aneurysm involves thrombus. Color Doppler US also aids in differentiating an aneurysm from a popliteal mass such as a Baker cyst. Conventional angiography can be ineffective in detecting PAA, particularly if the artery is occluded. MR imaging can be useful in delineating the aneurysmal sac and mural thrombus.

Thrombosis, distal embolization of thrombotic material, and, in rare cases, rupture can all complicate PAAs. According to studies, complications arise in 18%–31% of such aneurysms that are not surgically repaired. In patients with acute thrombosis, thrombolytic therapy is often used to recanalize the distal popliteal and trifurcation vessels as targets for bypass surgery. Despite the presence of thrombus within popliteal aneurysms, thrombolytic therapy is very effective in patients who can tolerate an additional duration of ischemia.

Asymptomatic PAAs are usually recommended to be fixed unless surgery will put the patient at high risk. This advice is focused on the high incidence of complications regardless of aneurysm size, the high amputation rate following complications, and the lower graft patency rate in patients who have encountered complications.

Trauma(knee joint & patella)

Because of its proximity to the distal femur and knee joint, the popliteal artery is vulnerable to damage. Popliteal artery damage is often associated with anterior and posterior knee dislocations, as well as fractures. Popliteal artery occlusion occurs in 30%–50% of patients with full knee dislocation. In today’s culture, such injuries are most often caused by motor vehicle collisions, but penetrating wound injuries are not uncommon. Laceration, dissection, occlusion, and posttraumatic pseudoaneurysm development are examples of traumatic injuries. An arteriovenous fistula may form when the popliteal artery and vein are injured.

Popliteal artery damage necessitates a high level of skepticism on the part of the clinician. Any traumatic knee injury should be followed by a careful arterial review of the affected extremity. Before the presentation, a knee may be dislocated and then moved. Furthermore, clinical results can be deceptive: distal pulses do not rule out popliteal artery damage, nor does regular distal capillary refill. Finally, a patient with a knee dislocation can need arteriography to rule out popliteal artery injury. The angiographic appearance of the artery can range from intimal dissection to full occlusion.

Patients who have suffered serious trauma and have visible arterial damage on clinical assessment will generally undergo surgery. Surgical treatment options include bypass grafting and patch angioplasty. Percutaneous therapy is currently not used in management. Again, prompt diagnosis and care are important for reducing morbidity and avoiding limb amputation.

Popliteal Artery Embolus

Embolism can affect the popliteal artery, just like any other peripheral artery. Macroemboli has a natural propensity to lodge in the popliteal artery, where it divides into the tibioperoneal trunk and the anterior tibial artery. A cardiac embolus is the most common cause of an embolus in the lower extremities. Aortic aneurysms and proximal arterial plaque or ulceration are two other possible causes.

Acute arterial embolism, regardless of the cause, almost always necessitates immediate care.

Acute signs of arterial embolism are present in patients. Pressure, pallor, pulselessness, paresthesia, and paralysis are the five cardinal signs and symptoms of arterial ischemia. The patient will feel intense rest pain if they have an occluding embolus. The lower leg and foot would be pale and devoid of pulses. If left untreated, the condition will progress to paresthesia and paralysis. Before angiography, a noninvasive arterial test can be performed. With acute occlusion, there could be a complete lack of Doppler signals at the ankle, making an ABI impossible to obtain. Color duplex the US can also be used to depict thrombus, but due to the acute clinical appearance, the patient will normally be referred for angiography. Thrombus in the popliteal artery manifests as a complete angiographic occlusion with the classic “meniscus sign,” a filling defect, or an abrupt vessel cutoff.

Systemic anticoagulation therapy, percutaneous thrombolytic therapy, surgical embolectomy, and mechanical thrombectomy are all options for treating acute embolism. The degree of ischemia that the patient is experiencing will always determine the course of treatment. Given the time it takes to conduct thrombolysis, surgical options may be more timely if the ischemia has worsened but is potentially reversible. Thrombolytic therapy is successful, with a low risk of hemorrhagic complications, and it decreases the need for surgical procedures with comparable limb salvage rates. Mechanical thrombectomy systems that decimate or suction the thrombus are used in other interventional techniques. For the best prognosis, treatment should begin within hours of the onset of symptoms.

Few Last Words

The popliteal artery is a deep artery and can be affected by several diseases and conditions. Amongst them the most common one is atherosclerosis. It affects usually older patients.

Last Updated on February 23, 2022 by Learn From Doctor Team