Table of Contents

Arterial Bleeding Overview

There are three types of bleeding. Arterial bleeding, Venous bleeding, and Capillary bleeding. In this article, we’ll discuss the arterial bleeding overview and how to stop them.

First Step to Stop Any Bleeding

- Apply direct pressure.

- Elevate the bleeding extremities if no obvious fracture or dislocation.

- Consider pressure points such as Axillary, brachial, femoral.

- Don’t try to remove impaled objects/material because the tamponade bleeding.

- Use a tourniquet if needed.

Read Seizure Precautions

Management of Arterial Bleeding in Upper Extremity

First Step

- Control the bleeding and, if necessary, concentrate on other, more serious injuries. Begin resuscitation if necessary.

- Every bleeding that occurs in an extremity can be stopped by pressing the specific points.

- You can use a tourniquet if there is insufficient manpower.

- Avoid clamping blindly because nerve fibers are bundled with vascular structures and are easily affected.

Read Venous Bleeding

Tourniquet Using Guide for bleeding management

|

Pneumatic Tourniquet |

Standard BP Cuff |

Standard Field Tourniquet |

|

|

|

- Consider elevating limbs before inflating. Try distal to proximal wrapping with a tight ACE wrap.

- The time of application must be recorded.

- Perform neurological examination and the mental status during the time of application.

- Do not leave the tourniquet for more than 120 minutes.

- If the patient is suffering from severe pain release the tourniquet.

Diagnose the Arterial Bleeding or Injury

Signs of Severe Arterial Injury

- Active hemorrhage

- Pulses may be absent

- Bruit or Thrill may present

- Signs of limb ischemia or compartment syndrome may present

- Pulsatile hematoma(sometimes expanding)’

Signs of Acute Arterial Injury

- Wound proximity to vascular structure

- Major single nerve deficit such as sciatic, femoral, median, etc.

- Non-expanding hematoma

- Diminished pulses

- Anterior elbow or posterior knee dislocation

- Hypotension and moderate blood loss at the wounded area.

If there are severe signs of arterial injury in a major artery, the patient will need surgical treatment.

Radiological examination is not necessary unless the site of the bleeding is obscured in a conscious patient.

Arterial Pressure Index

Arterial Injury in Upper Limb

- Place the patient in the supine position

- Place a normal BP cuff distal from the point of injury

- Use a doppler and inflate the cuff to 20 mmHg past the point where doppler sound is not anymore hearable.

- Release the pressure slowly and note the pressure(systolic blood pressure) when the doppler sound starts to appear.

- Repeat this process on the uninjured limb(upper)

- Calculation: Injured upper limb SBP/ Uninjured upper limb SBP

Arterial Injury in Lower Limb

- Repeat the process as upper limb

- Calculation: Injured lower limb SBP/ Uninjured lower limb SBP

Interpretation of Arterial Pressure Index

- If the API is greater than 0.9, the patient is doubtful to have an arterial injury. Observe or discharge depending on the severity of the injury/patient.

- If the API is less than 0.9, there is a chance of arterial injury. The patient will require further testing, preferably a CTA.

Importance of Arterial Pressure Index

In lower limb injuries, API is preferred over ABI (Ankle Brachial Index). Lower limb SBP is compared to brachial SBP by ABI. Patients typically have more atherosclerotic disease in their lower limbs than upper limbs, which may wrongly elevate their ABI and make the diagnosis of a vascular injury more difficult. The API, on the other hand, is based on the fact that the sum of atherosclerotic disease in the two uppers and two lower extremities is normally symmetric.

API is an excellent test. An API less than 0.9 has a specificity and sensitivity of 95 and 97 percent for major arterial injury, meanwhile, whereas an API higher than 0.9 has a negative predictive value of 99 percent.

Vessels Injury Inspection

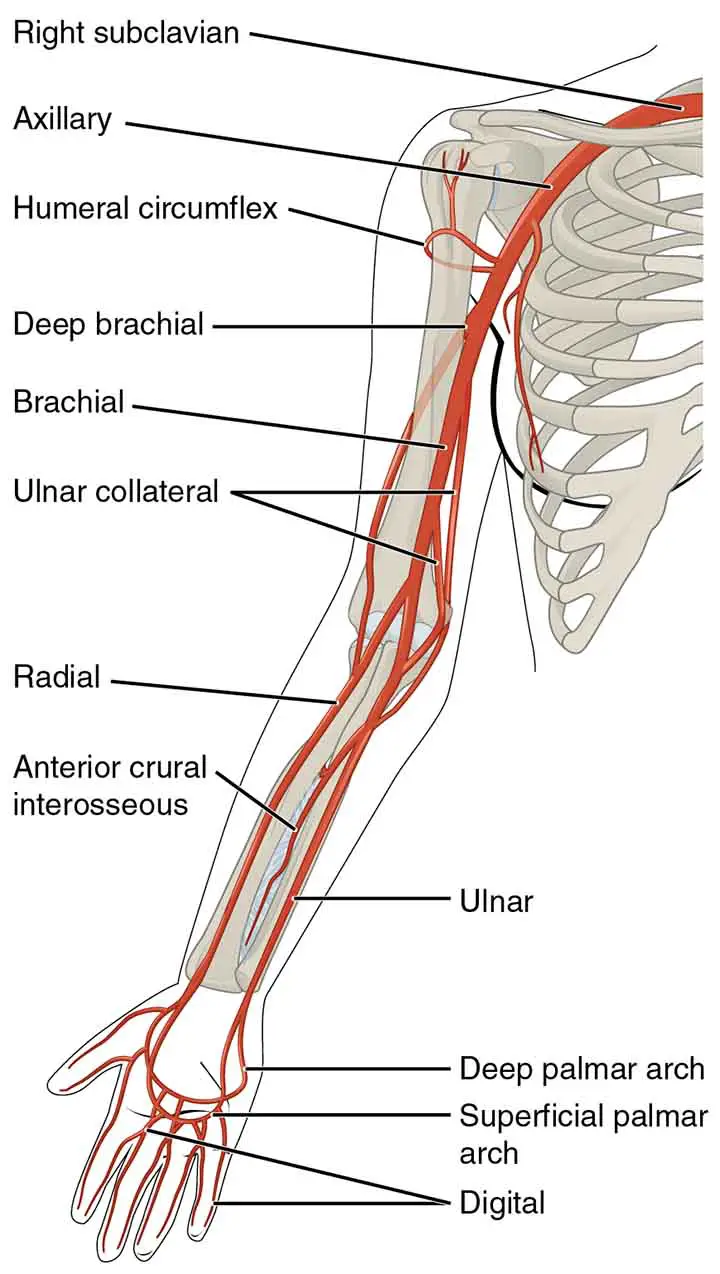

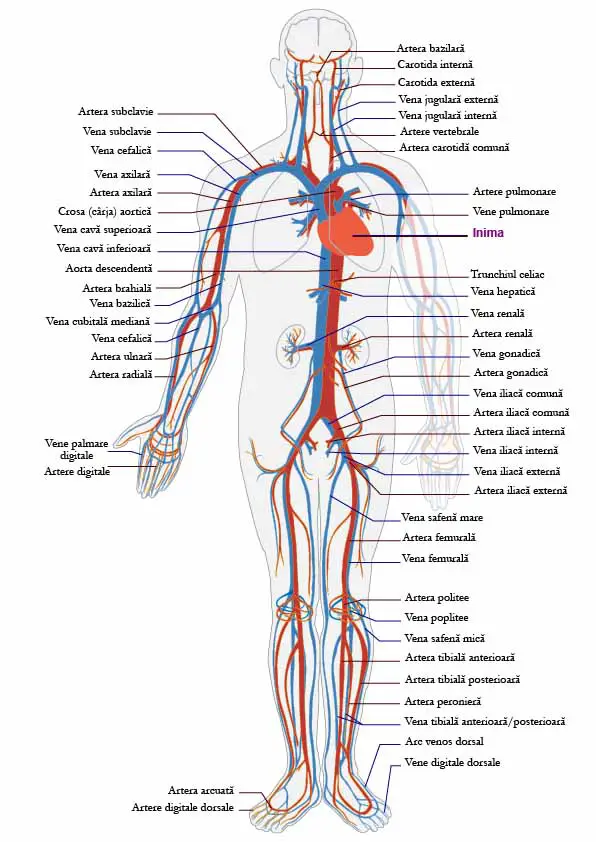

Arterial Supply of the Upper Limb

The arm or upper limb is supplied by 5 major arteries. These are

Proximal to distal;

- Subclavian artery

- Axillary artery

- Brachial artery

- Radial artery

- Ulnar artery

Subclavian Artery

The subclavian artery is the starting point for the arterial supply to the upper extremity. The brachiocephalic trunk gives rise to the subclavian artery on the right. It branches progressively from the aortic arch on the left.

The subclavian artery runs laterally from the neck to the axilla. It is divided into three sections based on its relationship to the anterior scalene muscle:

The 1st Part: Runs from the subclavian artery’s root to the medial border of the anterior scalene.

The 2nd Part: From the posterior to the anterior scalene.

The 3rd Part: Extends from the lateral border of the anterior scalene to the lateral border of the first rib.

Axillary Artery

The axillary sheath protects the axillary artery, which is located deep to the pectoralis minor (a fibrous layer that covers the artery and the three cords of the brachial plexus).

The artery can be mainly divided into 3 parts based on its location relative to the pectoralis minor muscle:

The 1st Part: Near to the pectoralis minor

The 2nd Part: From the posterior to the pectoralis minor

The 3rd Part: Proximal to pectoralis minor

Main branches of axillary artery

The 1st Part: Superior thoracic artery

The 2nd Part:

- Thoracoacromial artery

- Lateral thoracic artery

The 3rd Part:

- Subscapular artery

- Anterior and posterior circumflex arteries

Brachial Artery

The brachial artery is a branch of the axillary artery that extends beyond the lower boundary of the teres major. It is the primary source of blood for the arm.

The brachial artery provides branch – profunda brachii (deep artery) directly distal to the teres major, which passes with the radial nerve in the radial groove of the humerus and supplies the internal structures in the posterior part of the upper arm. The profunda brachii joins an anastomotic network that anatomically wraps around the elbow joint.

The brachial artery proper(main) runs down the sleeve of the arm. The brachial artery ends by bifurcating into the radial and ulnar arteries as it passes through the cubital fossa, beneath the bicipital aponeurosis.

Radial Artery and Ulnar Artery

The radial and ulnar arteries are the continuations of the brachial artery which bifurcated inside the cubital fossa.

Radial artery: It supplies the forearm’s posterolateral side. It helps to form anastomotic networks around the elbow joint and carpal bones.

The most important pulse, the radial pulse can be recorded in the distal forearm, just lateral to the prominent flexor carpi radialis tendon.

Ulnar artery: The anteromedial part of the forearm is supplied by the ulnar artery. It contributes to the formation of an anastomotic network around the elbow joint.

The anterior and posterior interosseous arteries are also created, which provide deeper structures in the forearm.

Radial and ulnar arteries together create two arches in the hand, the superficial palmar arch and the deep palmar arch.

The Superficial and Deep Palmer Arch

The hand has a well-developed arterial supply with numerous anastomoses between arteries. This helps the hand to be perfused even though there are comparatively high resistance and pressure (such as when grasping something or applying pressure).

The ulnar and radial arteries supply the hand with blood. The ulnar artery enters the hand anteriorly and laterally to the flexor retinaculum and the ulnar nerve. It gives rise to the superficial palmar arch and continues laterally across the palm as the deep palmar branch.

The radial artery enters the hand dorsally, crossing the anatomical snuffbox floor. It then turns medially and passes between the adductor pollicis muscle heads. The radial artery branches to the wrist, index finger, and the superficial palmar arch before continuing as the deep palmar arch.

As a result, two arterial arches develop:

The superficial palmar arch is located anteriorly to the hand’s flexor tendons and deep to the palmar aponeurosis. It is responsible for the formation of the digital arteries, which supply the four fingers.

The deep palmar arch is situated deep to the hand’s flexor tendons. It helps to supply blood to the digits and the wrist joint.

Arterial Supply of the Lower Limb

Femoral Artery

The femoral artery is the principal artery of the lower limb. It is a branch of the external iliac artery (terminal branch of the abdominal aorta). When the external iliac crosses the inguinal ligament and joins the femoral triangle, it becomes the femoral artery.

The profunda femoris artery emerges from the posterolateral part of the femoral artery in the femoral triangle. It flies posteriorly and distally, spawning three major branches:

- Perforating branches: Consists of three or four arteries that perforate the adductor Magnus, supplying the muscles in the medial and posterior thigh.

- The lateral femoral circumflex artery: Wraps around the anterior, lateral side of the femur, providing some of the lateral thigh muscles.

- The medial femoral circumflex artery: Wraps across the back of the femur, providing the neck and ears. This artery is easily crushed in a femoral neck fracture, resulting in avascular necrosis of the femur head.

The femoral artery proceeds down the anterior aspect of the thigh through the adductor canal while leaving the femoral triangle. The artery feeds the anterior thigh muscles as it descends.

The adductor canal terminates at a hole in the adductor Magnus is known as the adductor hiatus. The femoral artery passes through this opening and enters the thigh’s posterior compartment, proximal to the knee. The femoral artery has been renamed the popliteal artery.

Some Other Arteries of The Thigh

Other arteries supply the lower limb in addition to the femoral artery.

In the pelvic area, the obturator artery emerges from the central iliac artery. It descends through the obturator canal into the medial thigh, where it splits into two branches:

The anterior branch: The pectineus, obturator externus, adductor muscles, and gracilis are all supplied by this.

The posterior branch: Some of the deep gluteal muscles are supplied by this.

The superior and inferior gluteal arteries supply a significant portion of the gluteal area. These arteries branch off the internal iliac artery and join the gluteal area via the greater sciatic foramen.

The superior gluteal artery exits the foramen above the piriformis muscle, while the inferior gluteal artery exits below the muscle. The inferior gluteal artery, in addition to the gluteal muscles, extends to the vasculature of the posterior thigh.

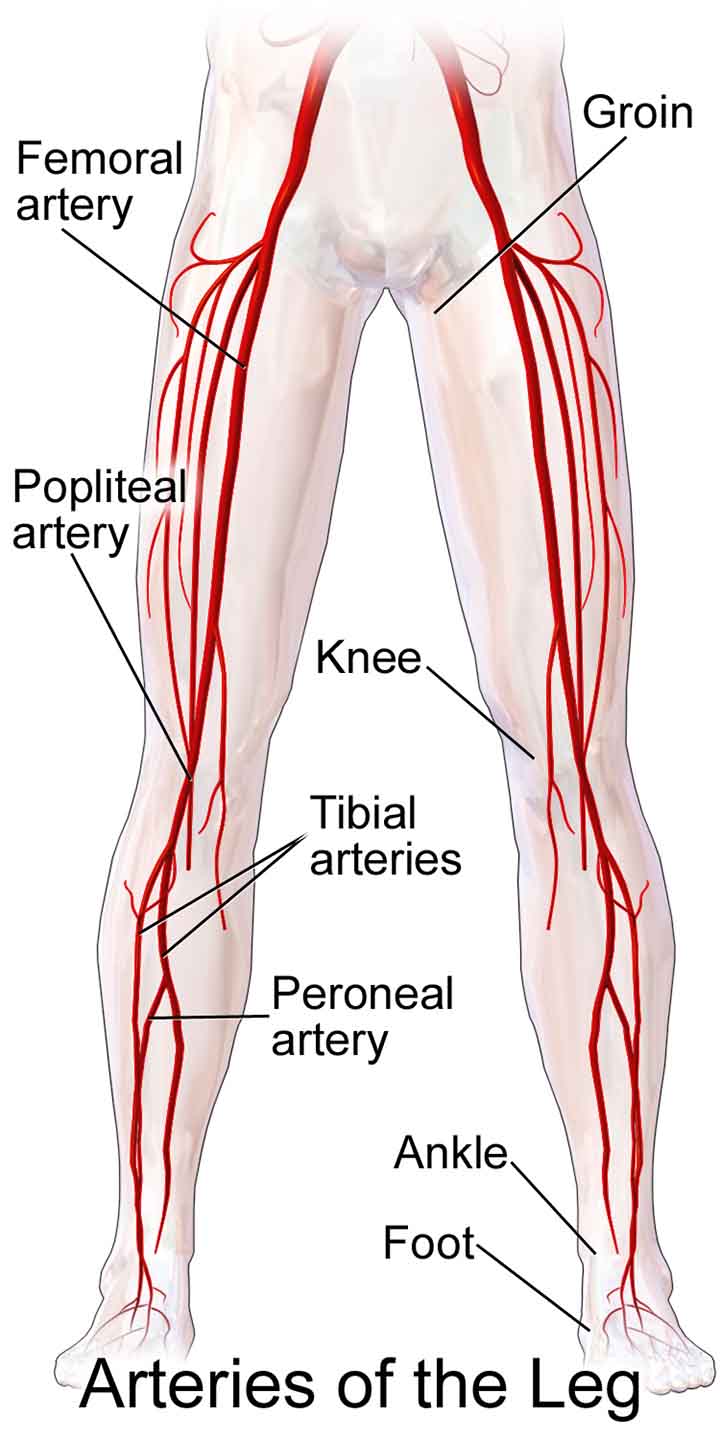

Arteries of the leg

The popliteal artery runs down the back of the thigh and gives rise to genicular branches that supply the knee joint. It exits between the gastrocnemius and popliteus muscles after passing through the popliteal fossa.

The popliteal artery divides into the anterior tibial artery and the tibioperoneal trunk at the lower boundary of the popliteus. The tibioperoneal trunk then divides into the posterior tibial and fibular arteries:

- The posterior tibial artery runs inferiorly along the surface of the deep posterior leg muscles (such as tibialis posterior). It reaches the sole through the tarsal tube, where it joins the tibial nerve.

- Fibular (peroneal) artery descends posteriorly to the fibula in the leg’s posterior compartment. It produces perforating branches that penetrate the intermuscular septum and supply muscles in the lateral compartment of the leg.

The anterior tibial artery, the other branch of the popliteal artery, runs anteriorly between the tibia and fibula through a gap in the interosseous membrane. It then moves lower down the leg. It extends the length of the leg and into the foot, where it merges with the dorsalis pedis artery.

Arterial Supply of the Foot

The arterial supply to the foot is provided by two arteries:

- Dorsalis pedis (a continuation of the anterior tibial artery)

- Posterior tibial

As the anterior tibial artery joins the foot, the dorsalis pedis artery begins. It travels over the dorsal aspect of the tarsal bones before moving inferiorly towards the foot’s sole. The deep plantar arch is formed as it anastomoses with the lateral plantar artery. The tarsal bones and the dorsal aspect of the metatarsals are supplied by the dorsalis pedis artery. It also helps to supply the toes through the deep plantar arch.

The tarsal tunnel is where the posterior tibial artery crosses the sole. After that, it divides into the lateral and medial plantar arteries. These arteries supply the plantar side of the foot and help to supply the toes through the deep plantar arch.

Examine The Extremities

During the excitement of pulsatile bleeding, it’s easy to skip/rush this step. However, after the bleeding has been managed, keep in mind that your extremities are much less picky about blood supply than your vital organs. You should take a few minutes to assess the neurovascular state of the distal limbs (blood supply, sensory and motor function, tendon integrity), as this will be critical for management decisions.

Nerve and tendon injuries are often associated with arterial injuries. Conduct a comprehensive evaluation.

The majority of disability caused by arterial injuries is caused by the accompanying nerve injury rather than the actual arterial injury.

Observe the Arterial Wound

- It is important to closely examine the wound to search for any structures that have been affected.

- Examine tendons and muscles by moving their associated joints through their full range of motion to look for partial lacerations that might have been pulled out of sight.

Arterial Bleeding Control and Management

Proximal Arterial Injury or Damage

Both brachial artery injuries would necessitate immediate treatment by a vascular surgeon.

- The “golden age” is 6-8 hours before ischemia-reperfusion damage threatens the limb’s viability. The extent of ischemia is determined by whether the damage is proximal or distal to the profunda brachii.

- Larger, more proximal arteries are rarely damaged alone, and almost all have nerve/tendon/muscle injuries that necessitate surgical repair.

Arterial Injury or Damage in Forearm and Hands

Many arterial injuries in/near the hand do not necessitate surgical repair because most people have very robust collaterals in the hand with the double vascular system from the radial and ulnar arteries.

Arterial Bleeding Management

These are applicable for any kind of arterial bleeding according to the situation.

Manual direct digital compression: 15 minutes of uninterrupted direct pressure is always sufficient on its own.

Application of a temporary tourniquet and wound closure with running non-absorbable suture, accompanied by lightweight compressive dressing. If the vessel is visible, tying it off can be attempted; however, blindly clamping/tying would most likely injure neighboring structures, especially nerves.

If the bleeding cannot be managed with the measures listed above, surgical repair may be necessary.

In the absence of acute hand ischemia, studies have shown that simple ligation of a lacerated radial or ulnar artery is both healthy and cost-effective.

Some surgeons, however, can also want to perform a primary repair.

Last Updated on February 23, 2022 by Learn From Doctor Team